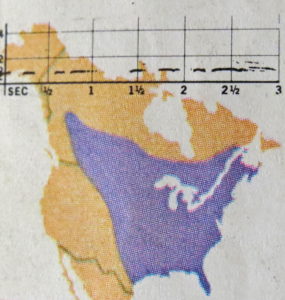

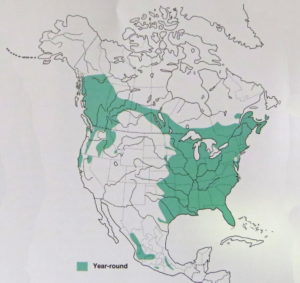

Since then, Barred Owls have moved south along the California coast to Sonoma and Marin Counties and into the California interior along the northernborder at Tule National Wildlife Reserve, Siskiyou and Modoc Counties, Nevada and Yuba Counties (north and northwest of Lake Tahoe), and Tulare County (General Grant Grove) through 2004. In 2012, one bird was photographed at Spanish Spring, eight miles NW of Sparks, Nevada (Janice Vitale, et al., North American Birds 67:321), a first record for the state. See map (below, left) from Mazur, K.M. and James, P.C. 2000. Barred Owl in Birds of North America, No. 508 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds. The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA).

You may question why you are reading this tutorial on the Barred Owl, which has not occured in Inyo County. So glad you asked!

From Mazur, K.M. and James, P.C. 2000. Barred Owl in Birds of North America, No. 508 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA

On 4 February 2016, Jen Scott, an Emergency Room physician at Northern Inyo Hospital, took her break as she usually does by walking in the COSA (Conservation Open Space Area) designed and managed by the Bishop Paiute Tribe. She noticed an owl perched in a tree behind the BLM/Forest Service building and looked hard at it. She knew it was an owl, but she’d never see this species before. She returned to the hospital to get her camera and walked back to the tree hoping it would still be there and she could get some images. It was, and she did. Break time over, she returned to work. It wasn’t until the evening she had time to call Nancy Overholtz, whom she had met on birding field trips, and said that she had an owl and didn’t know what species it was. Nancy asked if she could send an image, “Yes” said Jen. Nancy opened the image and responded, “WOW!” She checked her field guide to confirm her identification and then sent the image to us for another confirmation. It was an unequivocal image of a Barred Owl. Nancy called Jen and told her, “It’s a Barred Owl and it has never been recorded in Inyo County before!” Nancy immediately began calling some local birders to give them the exciting news and suggest that the following morning at 0730 they meet in the parking lot to the COSA.

On 5 February, twelve people arrived as the sun rose and quietly and slowly walked through the COSA gate and down the lane to the east and the BLM/Forest Service communications tower. As they closed in on the tree closest to the tower and were able to view the east side where Jen had it perched, disappointed sigh sounds emanated from the group. Jen Scott showed everybody the exact branch it was sitting on, but it was not there this morning. The group dispersed and for the next couple of hours scoured the COSA. The habitat is so extensive and the backs of some of the trees are hidden with other vegetation that the owl could have been there but not visible to all the adrenaline-driven eyes. For another couple of hours the group re-scoured the COSA and expanded coverage into the cemetery with the same results. Not to be deterred, plans were made to again look the following morning. On 6 February, Nancy and Ron have made an early morning survey for the owl part their daily schedule and post daily whether the owl was there or not. On 6 February, they were out first and let everybody know that it was not in its tree. Some birders throughout the day searched and found no owl.On 7 February, Steve Dickinson refound the owl on the same branch and the call and Eastern Sierra Birds post went out immediately. Sixteen birders arrived shortly and stood in awe as shutters flickered like movie cameras while pixels were collected of the first ever record of a Barred Owl in Inyo County. Based on the shape of the tail feathers, pointed, and pure white, the bird was hatched last spring and is an immature. The bird was not seen 8 February but was there in all its glory on the same branch on the 9th and 10th remaining all day as had been the pattern. On the 9th the Barred Owl was sitting in the large crotch of the tree instead of the left-side smaller branch. No one had any suspicion that something was unusual until it jumped with a clump of feathers hanging from its right foot. The attached object quickly disappeared from view when the owl resettled and began eating, and eating, and eating, and eating. Obviously the intake was more than a small passerine could provide. After almost an hour, the owl hopped over the edge of the crotch, still clutching the carcass and wings slightly open like the owl was screening the booty from our view and quickly jammed it in a small crevice under the crotch. During this quick transfer images were taken with hopes that someone captured something that would identify the entre. Nancy said that she felt it was a Sharp-shinned Hawk but hoped the images would prove it. We sent images with some feathers and legs showing to some top-notch birders and their separate responses were identical ‘My gut tells me it is a Sharp-shinned Hawk but I wouldn’t bet my life on it!’ When top birders all “guess” the same answer, the preponderance of opinions makes calling it anything else absurd. No feathers of the victim have been recovered. The bird continued eating the carcass on the 10th and then was not observed for the next three days.

Guy McCaskie, the father of avian field observations and record keeping, as are practiced by today’s serious birders, came up from San Diego on the chance that it was going to reappear. It took three days but prescient, as he always has been, he saw the Barred Owl on the 14th, his last day. We arrived at the COSA with Guy at 0630 and no owl. Oh, the agony of defeat! We were so disappointed that today wasn’t going to be the day. Guy said he wanted to check out the tower to the east to see if he could find the second Peregrine Falcon because he could see one bird and there were two birds previously. We didn’t find a second Peregrine but we did get very close looks at an immature Northern Harrier that didn’t mind us coming close to him. Then Guy said he was ready to head home so we made a U-turn and headed back. As we reached the ‘T’ in the road we heard Guy excitedly say, “There is a bump on that branch!” and then “It’s the Barred Owl!!” Ecstatic juices flowed and three oldsters quickly reverted to being youngsters again! Oh Happy Days!! Calls and posts went out and other birders descended to join the party. After an hour, Guy reluctantly said he had to hit the road and beat the traffic home. That is one Valentine’s gift that will be forever remembered!

This saga continues and there is much to be learned by this Barred Owl, the southernmost interior record in California, and the first record for Southern California… so far.

Tags: hawk, owl