Although not a ‘proper’ flycatcher in the flycatcher family Tyrannidae, the Phainopepla is in a family called Ptilogonatidae commonly referred to as Silky-Flycatchers but more closely related to Bulbuls. Of the four species in the world, only two are found in North America and the other two are south to Panama. The most fascinating thing is that with all the bird studies over the last two centuries there is a mystery regarding their breeding behavior.

Phainopeplas are native to the Southwest United States and much of Mexico. In the deserts where their favorite food source, the mistletoe berry, is plentiful, the Phainopepla is common. In Inyo County, mistletoe berries abound in the southeast corner with many records from the Amargosa drainage, China Ranch, Crystal Spring, Death Valley Junction, Resting Springs, Shoshone, and Tecopa. But we also have records from Death Valley National Park and the Owens Valley, places with few if any mistletoe berries. Intriguing, huh!

Tecopa Triangle

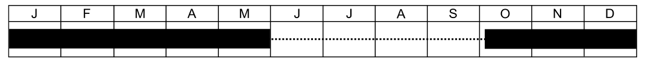

Sadly, banding data do not exist for Inyo County and none have been cited in the many articles we’ve read. Maybe we’ve missed the one that has the answer!?! We can say that Phainopepla are common in the “Tecopa triangle” from October through May and are rare to zero June through September. Breeding data exist January through March with large numbers of families in April, decreasing in May, and then bye-bye.

Distribution Graph for Phainopepla showing October-May abundance in Tecopa

Death Valley National Park

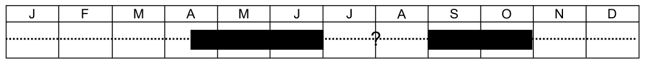

But wait, what is happening in Death Valley National Park? A few records occur November through April, numbers increase significantly in late April through June, highly reduced in July and August, increase again in September and October. Remember that data is the result of two entities…a bird and a birder. July and August are months with few birders in the Park so the few data reflects that reality, not the fact that Phainopepla are gone, but they might be. Breeding in the Park is documented in May and June.

Distribution Graph for Phainopepla showing mid-April through June, and September-October abundance in Death Valley

Owens Valley and Adjacent Mountains

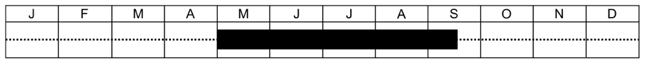

And then there is the Owens Valley and adjacent mountains with a nice supply of bird data gatherers… sometimes called birders but who work harder documenting what they find. Few records have been collected from October through April and this is indicative of reality since bird data gatherers bird all year! Then in May the shiny black and garnet objects arrive! Breeding is primarily May through July with departure about mid September. Breeding locations are Ninemile Canyon in the southern Sierra Nevada, Hogback and Lone Pine Creeks and Edward’s Field near Lone Pine, near Big Pine, and Owens River and Birchim Canyon both north of Bishop.

Distribution Graph for Phainopepla showing May through mid-September abundance in the Owens Valley

So there is a clear picture of when and where the Phainopepla are and when they breed. But some authors are beginning to question the conventional wisdom that they breed in deserts and then move up into riparian woodlands and oaks and breed again. That’s an intuitive answer. But where’s the proof? It has been suggested that these could be two populations in Mexico with one population moving into the deserts early in the season to breed and then return to Mexico as the second population moves into the more northern, cooler and more moist habitats to breed and then depart to the southern U.S. and Mexico to spend the winter.

As if that isn’t fascinating enough! The desert breeding Phainopepla defend their territories like terriers and beware any intruders. The more northern breeding Phainopepla believe in kum-ba-yah and nest in loose colonies, have overlapping home ranges, and join together to mob species like Scrub-Jays. “The question of whether the remarkable behavioral flexibility of the Phainopepla is exhibited by individuals or by separate populations of birds remains an unresolved and pressing issue.” This paragraph thanks to Chu and Walsberg 1999:2.

It seems that the solution is so simple! Band-em! Band them in the Tecopa triangle and then pack up your nets, poles, and boxes and move to the Owens Valley. Anybody need a Masters or PhD in Biology?

Chu, M. and Walsberg, G. 1999. Phainopepla (Phainopepla nitens). In The Birds of North America, No. 415 (A. Poole and F. Gill, etd.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Tags: flycatcher